The Artist of

POSSIBILITY

Magazine

In my review of Steven Kotler's book The Rise of Superman, we looked at a Western psychological conception of flow. Now, we will explore a more Eastern conception on this topic; one that has been articulated centuries ago in foundational texts of Chinese philosophy.

In this essay, we will take a close look at Edward Slingerland's book Tying Not To Try: The Art and Science of Spontaneity, with additional insights from an interview that we conducted with the author. Slingerland is a professor of Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia. One of his areas of concentration is Chinese thought and religious studies.

Interviews

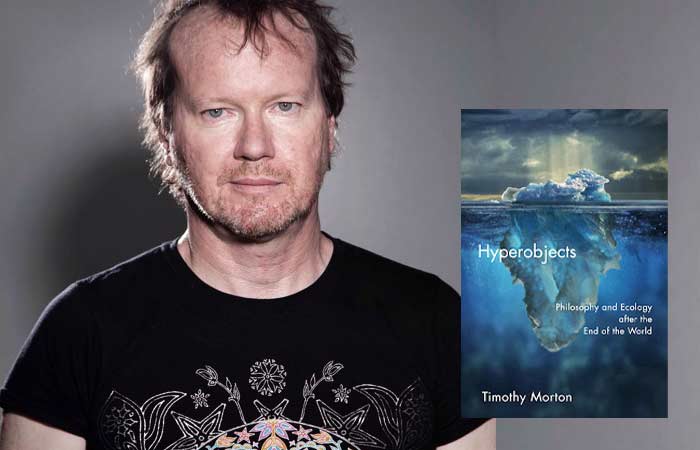

Hyperobjects and the Higher Dimension of Jesus

An Interview with Dr. Timothy Morton

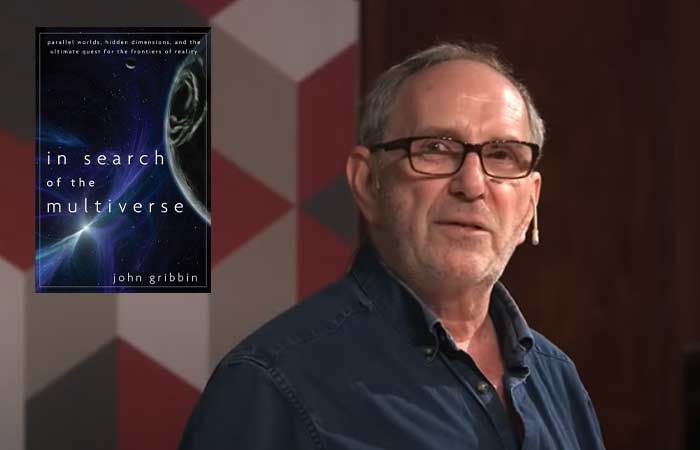

The Reality of the Multiverse

An Interview with John Gribbin

The Reality of the Fourth Dimension

An Interview with Rudy Rucker

The Awakening Power of Sleep and Dreams

An Interview with Athena Laz

An Introduction to Yoga Nidra

An Interview with Dharma MittraBook Reviews

A Summary of the Fetzer Institute’s Sharing Spiritual Heritage Report: An Review By Ariela Cohen and Robin Beck

By Ariela Cohen

Choosing Earth, Choosing Us: A Book Review of Choosing Earth

By Robin Beck

Monk and Robot: A Book Review

By Robin Beck

No Pallatives. No Promises: Radical acceptance as one woman's path to living with grief

By Amy Edelstein

Freed Freedom: Letters from a Sri Lanka Seeker to her Meditation Master

By Amy EdelsteinEssays

Bio-Psycho-Spiritual Foundations of Self-Realization: Reflections on being an Artist of Possibility and Transdimensional Spirituality

By KD Meyers

Awakening Through the Body

By Adriana Colotti Comel

What is Love? An Introspection

By Judith Marsden

Traditions are meant to be updated

By Olivia Wu