The Artist of

POSSIBILITY

Magazine

Knowing that we were going to dedicate this issue to magic, mysticism and the paranormal, meant that I had to speak with Dr. Jeffrey Kripal. Jeffrey is the J. Newton Rayzor Chair in Philosophy and Religious Thought at Rice University in Houston, Texas. Through Jeffrey's books, I have found a profound co-creative vision of reality in which our paranormal and mystical experiences are writing themselves into existence by inspiring us to write about them. Over the past few years, Jeffrey has become an important mentor to me. Reading his books and our various conversations have had a deep impact on my understanding and teaching. It is a pleasure to share this written piece that was edited from one of our many recorded dialogues.

Interviews

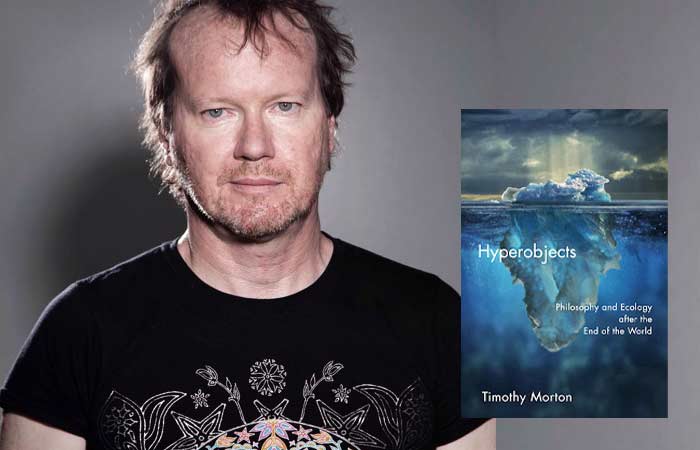

Hyperobjects and the Higher Dimension of Jesus

An Interview with Dr. Timothy Morton

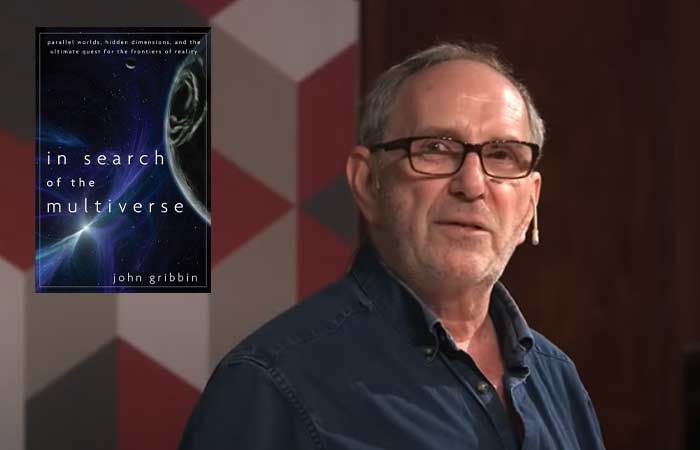

The Reality of the Multiverse

An Interview with John Gribbin

The Reality of the Fourth Dimension

An Interview with Rudy Rucker

The Awakening Power of Sleep and Dreams

An Interview with Athena Laz

An Introduction to Yoga Nidra

An Interview with Dharma MittraBook Reviews

A Summary of the Fetzer Institute’s Sharing Spiritual Heritage Report: An Review By Ariela Cohen and Robin Beck

By Ariela Cohen

Choosing Earth, Choosing Us: A Book Review of Choosing Earth

By Robin Beck

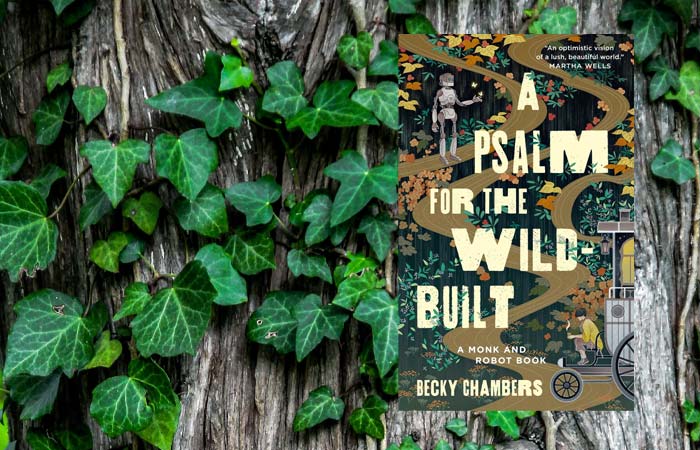

Monk and Robot: A Book Review

By Robin Beck

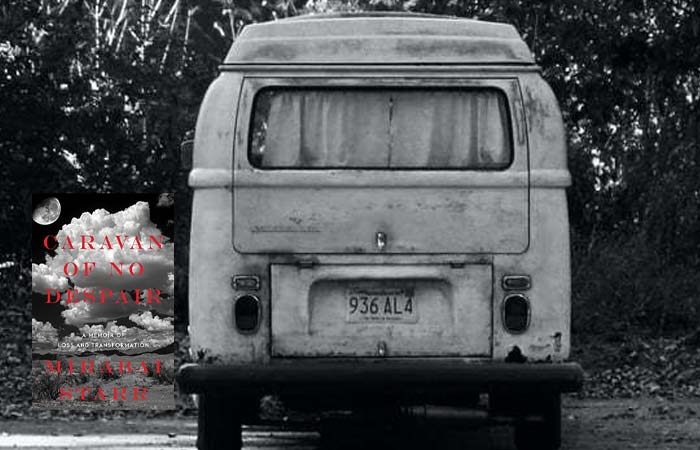

No Pallatives. No Promises: Radical acceptance as one woman's path to living with grief

By Amy Edelstein

Freed Freedom: Letters from a Sri Lanka Seeker to her Meditation Master

By Amy EdelsteinEssays

Bio-Psycho-Spiritual Foundations of Self-Realization: Reflections on being an Artist of Possibility and Transdimensional Spirituality

By KD Meyers

Awakening Through the Body

By Adriana Colotti Comel

What is Love? An Introspection

By Judith Marsden

Traditions are meant to be updated

By Olivia Wu